ACS Multimedia Atlas of Surgery: Pancreas Surgery Volume

Editors: Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS

| Product Details | |

| Year Produced: | 2010 |

| Pages: | 397 |

| Dimensions: | 8.75x11.15 in |

| ISBN: | 978-1-880696-43-9 |

Includes book with full online access to all chapters. Price includes shipping costs.

For assistance, comments, or questions, contact Olivier Petinaux, Senior Manager, Distance Education and E-Learning, elearning@facs.org or call us at 1-866-475-4696

The American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Ciné-Med have developed the interactive Multimedia Atlas of Surgery: Pancreas Surgery Volume.

A comprehensive atlas style text, this volume includes 36 chapters presenting both open and laparoscopic surgical techniques for treating pancreatic disease states. Expert surgeons provide detailed, step-by-step instruction using a combination of video, illustration, and intraoperative photos to clarify specific points of each procedure.

The text opens with an illustrated review of the pancreas anatomy with an outline of surgical approaches, exposure, and mobilization. Most of the chapters include discussion on diagnostic procedures, patient selection and evaluation, patient positioning, and port placement in addition to the detailed outline of the procedure.

Disease States:

- Necrotizing Pancreatitis

- Pancreatic Pseudocysts

- Islet Tumors/ Ampullary Tumors/ Cystic Lesions

- Adenocarcinoma

- Gastrinoma

Procedures:

- Cystgastrostomy

- Pancreaticojejunostomy

- Pancreatectomy

- Pancreatic Head Resection

- Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Individual titles are available for purchase. Select one below.

- Surgical Anatomy of the Pancreas

Alberto R. Ferreres, MD, PhD, MPH, FACS; Eduardo A. Pro, MD; Fernando Casal; Luis Alberto Carlos Lopolito, MD; Juan M. Verde, MD - Endoscopic Ultrasound of Pancreatic Lesions: Diagnosis and Treatment

Michael B. Wallace, MD, MPH; Muhammad Khalid Hasan, MD - Open Debridement for Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Elisabeth T. Tracy, MD; Theodore N. Pappas, MD, FACS - Minimally Invasive Approaches to Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Patrick S. Wolf, MD; Karen D. Horvath, MD, FACS - Open Cystogastrostomy for Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS; Christopher Solis, MD, FACS; CK Chang, MD, FACS - Endoluminal Approaches to Pancreatic Pseudocyst

Mehrdad Nikfarjam, MD, PhD, FRACS; Jeffrey L. Ponsky, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Management of Pancreatic Pseudocysts

Martin Palavecino, MD; Juan Pekolj, MD, PhD, FACS - Laparoscopic Lateral Pancreatojejunostomy for Chronic Pancreatitis

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; Steven P. Bowers, MD; Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS - Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Duodenum-Preserving Pancreatic Head Resection and Total Pancreatectomy

Dilip Parekh, MBBCh, FACS; Kaylene Berrera, MS - Duodenum-Preserving Subtotal and Total Resection of the Pancreatic Head

Hans Gunther Beger, MD, FACS; Steffen Gloekler, MD; Frank Gansauge, MD; Michael Schwarz, MD; Frans Poch; Bertram Poch, MD, PhD - Pancreatic Head Resection and Pancreaticojejunostomy for Chronic Pancreatitis

Howard A. Reber, MD, FACS; Jakob R. Izbicki, MD, FACS; Emre F. Yekebas, MD, FACS; Dana K. Andersen, MD, FACS; Christopher L. Wolfgang, MD, PhD, FACS; W. Scott Helton, MD, FACS; Charles F. Frey, MD, FACS - Open Surgical Approach to Islet Cell Tumors of the Pancreas

Courtney L. Scaife, MD, FACS; Sean J. Mulvihill, MD, FACS - Minimal-Access Approaches to Benign-Appearing Cystic Lesions of the Pancreas

Attila Nakeeb, MD, FACS - Surgery in the Treatment of Gastrinoma

E. Christopher Ellison, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Management of Pancreatic Islet Cell Neoplasms

Quan-Yang Duh, MD, FACS; Insoo Suh, MD - Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomy

Catherine Hubert, MD; Jean-Francois Gigot, MD, PhD, FRCS - Laparoscopic Spleen-Preserving Distal Pancreatectomy (LSPDP)

Pedro A. Ferraina, MD, FACS; Anibal Ariel Ferraro, MD - Laparoscopic Robotically-Assisted Distal Pancreatic Resection With Splenectomy

Sebastian V. Demyttenaere, MD, MSc; W. Scott Melvin, MD, FACS - Results of RAMPS Procedure for Adenocarcinoma of the Body and Tail of the Pancreas

Steven M. Strasberg, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Subtotal Pancreatectomy/Splenectomy

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS - Central Pancreatectomy With Transgastric Pancreatogastrostomy

Carlos F. Fernandez-del Castillo, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Central Pancreatectomy With Pancreatogastrostomy

Nicholas O'Rourke, MBBS, FRACS - Pancreatic Enucleation/Resection of Uncinate Lesions

R. Matthew Walsh, MD, FACS - Laparoscopic Robotic-Assisted Resection of Ampullary Tumors

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; Murali N. Naidu, MD; Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS - Rationale and Surgical Technique of Lymphadenectomy Associated With Duodenopancreatectomy for Pancreatic Head Carcinoma

Roberto Coppola, MD, FACS; Domenico Borzomati, MD, PhD, FACS; Sergio Valeri, MD; Alessandro Coppola, MD - Pancreaticoduodenectomy With Duct-to-Mucosa Pancreaticojejunostomy

Andrew L. Warshaw, MD, FACS; Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo, MD, FACS - Pylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy With Invaginating Pancreaticojejunostomy

Harish Lavu, MD; Jennifer Brumbaugh, MA; Charles J. Yeo, MD, FACS - Technique of Pylorus-Preserving Pancreaticoduodenectomy Using the Surgical Microscope for Pancreaticojejunostomy

L. William Traverso, MD, FACS - A Whipple Pancreaticoduodenectomy Associated With "en monobloc" Mesenterico-Portal Vein Resection

Philippe Bachellier, MD, PhD; Elie Housseau, MD; Daniel Jaeck, MD, PhD, FRCS - Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; John A. Stauffer, MD - Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy With Gastrojejunostomy Reconstruction

Chinnusamy Palanivelu, MCh, FRCS, FACS - Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy With Superior Mesenteric Artery Approach

Brice Gayet, MD, PhD; Zahra Shafaee, MD - Laparobotic Pancreatoduodenectomy: Caudad to Cephalad Approach

Anusak Yiengpruksawan, MD, FACS; Nino Carnevale, MD, FACS - Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Pancreaticoduodenectomy

Pier Cristoforo Giulianotti, MD; Francesco M. Bianco, MD; Fabio Sbrana, MD - Laparoscopic Total Pancreatectomy/Splenectomy

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; John Stauffer, MD - Laparoscopic Pancreas-Preserving Duodenectomy With Invaginating Pancreatojejunostomy and Gastrojejunostomy

Manpreet S. Grewal, MD; Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS; Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS

Horacio J. Asbun, MD, FACS

Philippe Bachellier, MD, PhD

Hans Gunther Beger, MD, FACS

Kaylene Berrera, MS

Francesco M. Bianco, MD

Domenico Borzomati, MD, PhD, FACS

Steven P. Bowers, MD

Jennifer Brumbaugh, MA

Nino Carnevale, MD, FACS

Fernando Casal

CK Chang, MD, FACS

Alessandro Coppola, MD

Roberto Coppola, MD, FACS

Sebastian V. Demyttenaere, MD, MSc

Quan-Yang Duh, MD, FACS

E. Christopher Ellison, MD, FACS

Carlos F. Fernandez-del Castillo, MD, FACS

Pedro A. Ferraina, MD, FACS

Anibal Ariel Ferraro, MD

Alberto R. Ferreres, MD, PhD, MPH, FACS

Charles F. Frey, MD, FACS

Pascal R. Fuchshuber, MD, PhD, FACS

Frank Gansauge, MD

Brice Gayet, MD, PhD

Jean-Francois Gigot, MD, PhD, FRCS

Pier Cristoforo Giulianotti, MD

Steffen Gloekler, MD

Manpreet S. Grewal, MD

Muhammad K. Hasan, MD

W. Scott Helton, MD, FACS

Karen D. Horvath, MD, FACS

Elie Housseau, MD

Catherine Hubert, MD

Jakob R. Izbicki, MD, FACS

Daniel Jaeck, MD, PhD, FRCS

Harish Lavu, MD

Luis Alberto Carlos Lopolito, MD

W. Scott Melvin, MD, FACS

Sean J. Mulvihill, MD, FACS

Murali N. Naidu, MD

Attila Nakeeb, MD, FACS

Mehrdad Nikfarjam, MD, PhD, FRACS

Nicholas O'Rourke, MBBS, FRACS

Chinnusamy Palanivelu, Mch, FACS

Martin Palavecino, MD

Theodore N. Pappas, MD, FACS

Dilip Parekh, MBBCh, FACS

Juan Pekolj, MD, PhD, FACS

Bertram Poch, MD, PhD

Frans Poch

Jeffrey L. Ponsky, MD, FACS

Eduardo A. Pro, MD

Howard A. Reber, MD, FACS

Fabio Sbrana, MD

Courtney L. Scaife, MD, FACS

Michael Schwarz, MD

Zahra Shafaee, MD

Christopher Solis, MD, FACS

John A. Stauffer, MD

Steven M. Strasberg, MD, FACS

Insoo Suh, MD

Elisabeth T. Tracy, MD

L. William Traverso, MD, FACS

Sergio Valeri, MD

Juan M. Verde, MD

Michael B. Wallace, MD, MPH

R. Matthew Walsh, MD, FACS

Andrew L. Warshaw, MD, FACS

Patrick S. Wolf, MD

Christopher L. Wolfgang, MD, PhD, FACS

Emre F. Yekebas, MD, FACS

Charles J. Yeo, MD, FACS

Anusak Yiengpruksawan, MD, FACS

Acute pancreatitis is a common diagnosis, affecting nearly 200,000 patients each year in the United States (1). The majority of these patients have only a mild form of disease, manifest by transient abdominal pain, anorexia, and prompt resolution of symptoms with conservative management. Severe acute pancreatitis, complicated by peripancreatic fat necrosis, fluid collections, and/or pancreatic gland necrosis, occurs in only 10% of patients, but significantly increases morbidity and mortality. For the purposes of this chapter, this disease process and various complications will be collectively referred to as "necrotizing pancreatitis." Walled-off necrosis can be further complicated by infection, necessitating complete and effective drainage. Drainage procedures may be required for some patients with sterile necrosis, but this is an area of controversy that will not be addressed in this chapter. (See Chapter 7 for more on pancreatic pseudocysts.)

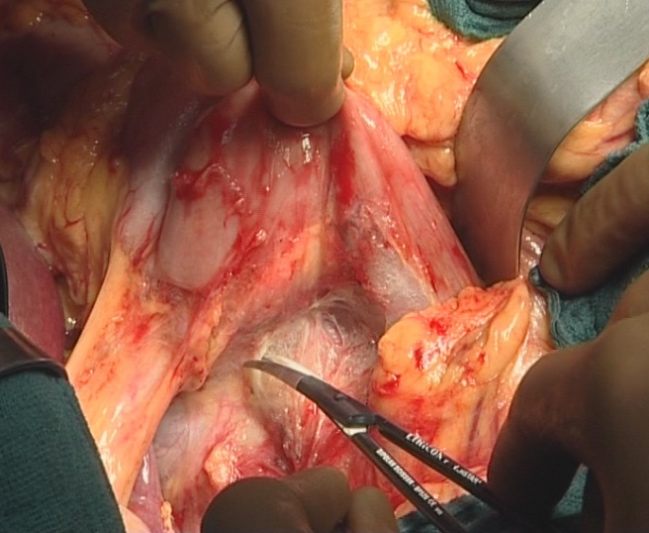

Once infection has occurred, whether via natural means (e.g., gut translocation) or iatrogenic means (e.g., endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP] or placement of a drain into a sterile collection), effective drainage is required. Different methods of drainage include open necrosectomy techniques, percutaneous drainage, and endoscopic methods. Our video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD) technique was developed to incorporate the benefits associated with open necrosectomy while minimizing the adverse effects of an open operation through the use of debridement under direct visualization with a laparoscope.

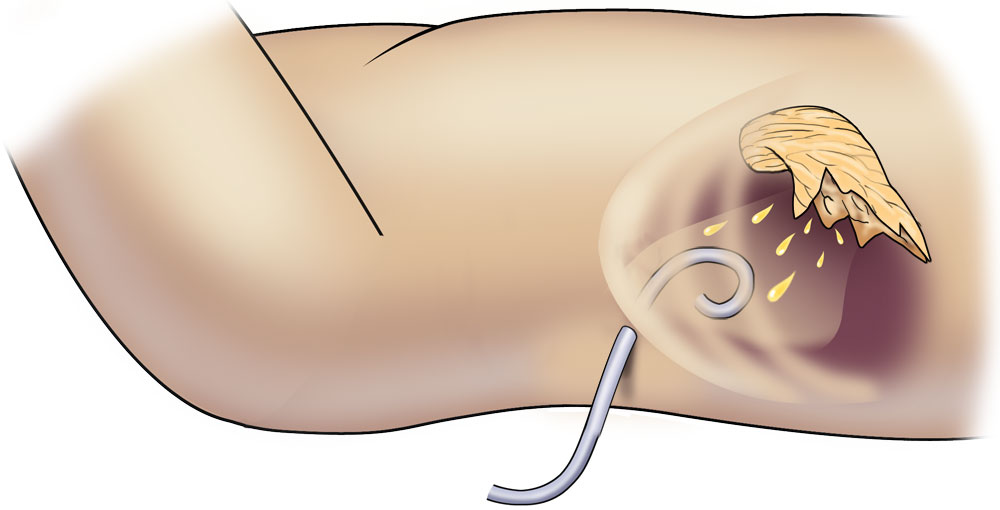

Early operative intervention in patients with pancreatic necrosis is now reserved for very select cases in which specific criteria for operation are met, including concern for concomitant intra-abdominal catastrophe or rapid and life-threatening clinical deterioration despite maximal medical care (2). In the absence of these criteria, patients with necrotizing pancreatitis should be initially managed with aggressive, supportive medical care, maximizing cardiopulmonary and nutritional support. Numerous studies support continuing this supportive approach for at least 4 weeks after disease onset to allow acute peripancreatic fluid collections to resolve or mature into the more chronic phase of walled-off necrosis3,4. Any patient with necrotizing pancreatitis that has a clinical deterioration at any time, such as a new fever or leukocytosis, warrants aggressive workup for infected necrosis. Findings indicative of infection include a positive Gram stain or culture on fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the pancreatic collection or retroperitoneal gas on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan. Fine needle aspiration can be repeated at weekly intervals if clinically indicated, with high sensitivity and specificity and low risk for superinfection5. Once an infection is diagnosed, percutaneous drainage catheter placement is performed with the help of interventional radiology (Figure 1).

In almost all circumstances, percutaneous drainage effectively temporizes the patient's clinical condition. It is important to delay operative intervention for at least 4 weeks from the time of initial symptom onset to allow the cavity wall to fully mature and the necrotic tissue to demarcate, thus making VARD technically safer and more effective3,4.

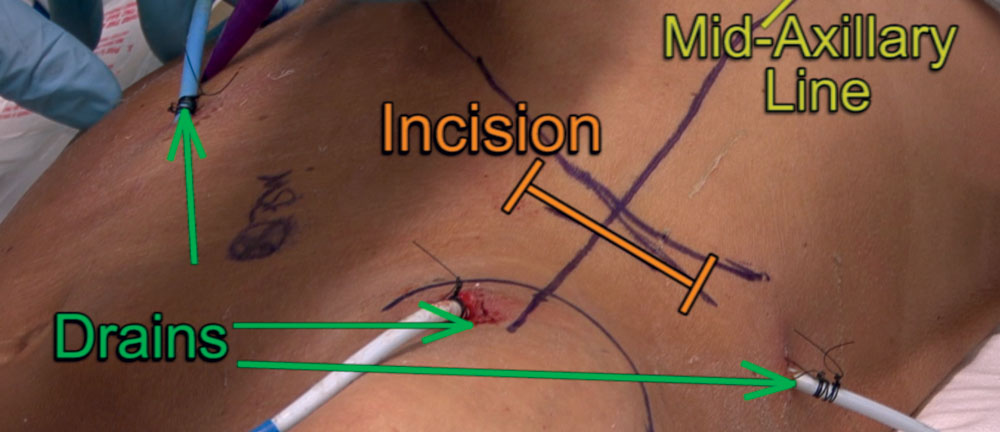

Once a percutaneous drain has been placed, aggressive upsizing to 18- to 20-Fr catheters is performed every 3 to 4 days. A CT is repeated 10 to 14 days later. If the patient has a remaining large collection and a minimum of 4 weeks have elapsed since onset of disease, plans are made for a VARD. If not already present, a percutaneous drain should be placed as close as possible to the left costal margin at the midaxillary line (Figure 2).

This drain will be used as a digital guide to access the collection in the operating room (OR). A CT scan should be repeated after this drain is in place. The CT image will serve as a guide for the surgeon in the OR to identify the correct path into the abscess cavity. These are crucial steps that are absolutely necessary for a successful VARD procedure. Two additional steps include having an open laparotomy set and 4 units of cross-matched blood available in the OR. Although bleeding complications are exceedingly rare, there is potential for significant blood loss if they do occur.

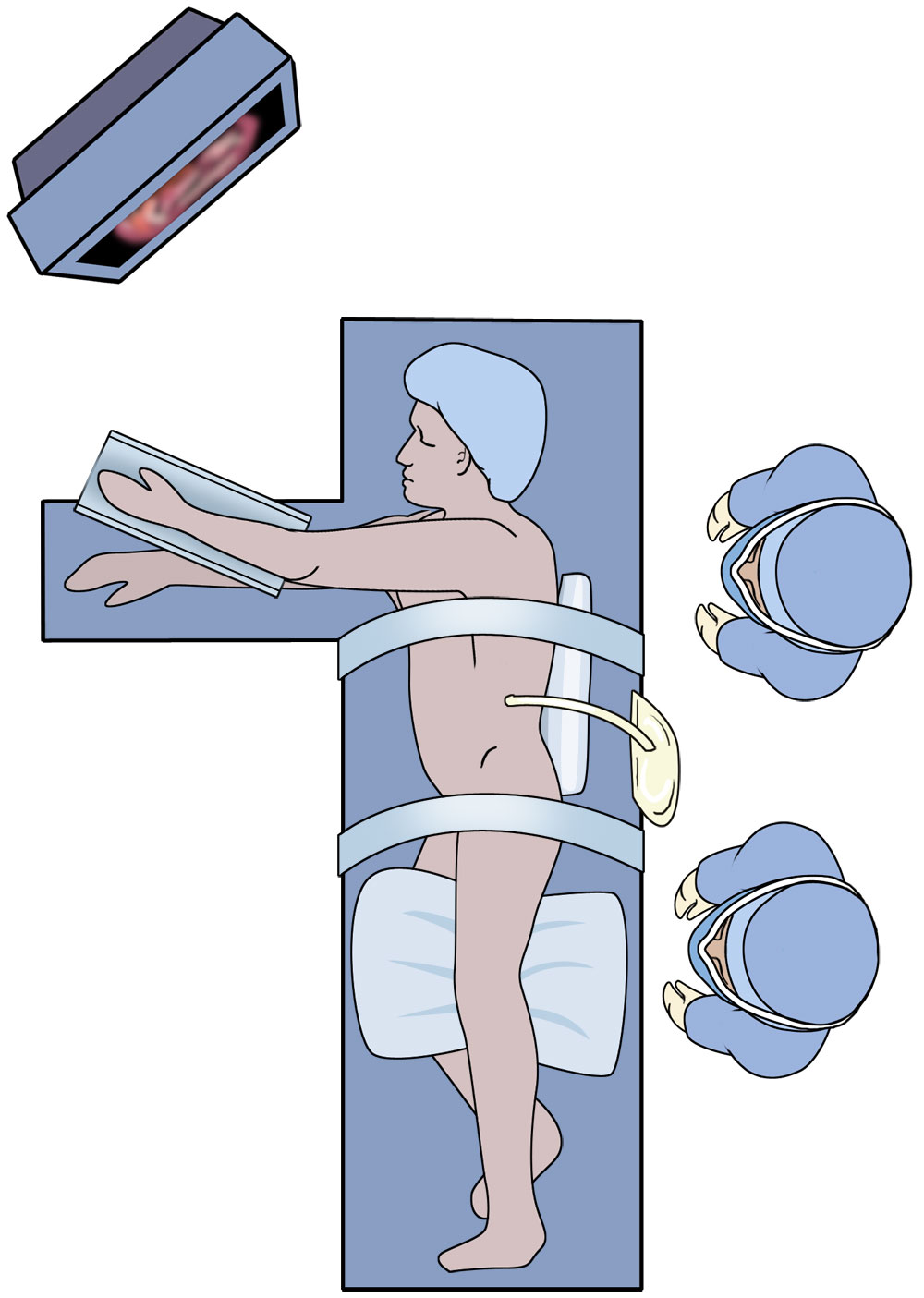

The setup of the operating room is depicted in Figure 3, with the patient positioned with a roll under the left flank and the monitor at the patient's right. Both surgeon and assistant will stand to the patient's left.

The patient is placed in a modified right lateral decubitus position at about 30 degrees with the aid of a roll under the left flank. It is important that the patient is placed over the kidney flex in the bed to facilitate opening of the costal margin. For obese patients, a beanbag may be needed to help stabilize the patient. The left arm is strapped into an airplane device. A chest and lower extremity strap are placed, and the patient is taped into position since extreme table angles may be used.

Sequential compression devices and an active body-warming device are placed. An important step prior to draping is to mark several important anatomic landmarks: the bilateral costal margins, the xiphoid, the anterior superior iliac spine, the midaxillary line, and the planned incision site. Once the patient is draped, it can be difficult to accurately determine these important landmarks (Figure 4).

The left costal margin at the midaxillary line is the location for the incision. The midaxillary line generally approximates the junction of the posterior peritoneal sac and the retroperitoneum where access is gained into the collection.

The table is placed into reverse Trendelenburg and rolled right side down about 15 to 30 degrees. The entire abdomen and left flank, including the percutaneous drains, are prepped into the field from nipple to pubis, and table to table.

Should rapid conversion to an open laparotomy be required, the bed can be rotated to neutral and the previously marked anatomic landmarks will be helpful.

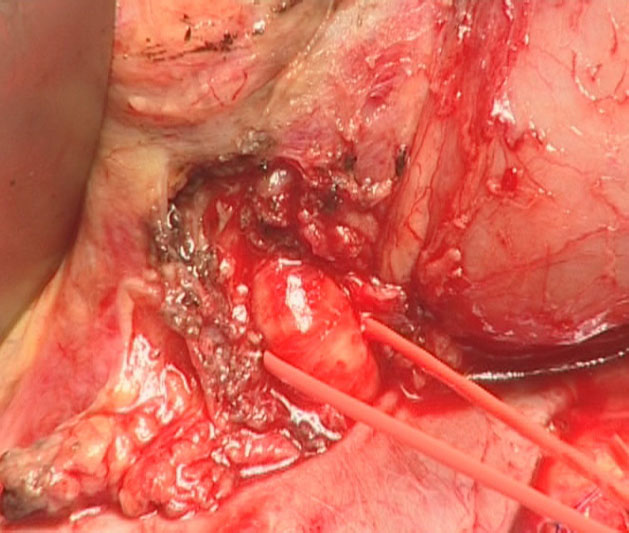

Pancreaticoduodenectomy was first described as a two-stage operation in 1935 by Whipple. It has evolved into a one-stage procedure, which is often combined with an extensive lymphadenectomy and an additional mesenterico-portal vein resection to achieve R0 resection and adequate staging. For these reasons, a pancreatic resection remains a meticulous and demanding operation requiring training and surgical skills in gastrointestinal and vascular surgery. Pancreatic cancer has the worst prognosis of all gastrointestinal carcinomas, and surgical resection offers the only chance for cure. However, long-term survival and a cure are achieved in only 10% to 15% of the patients. Failure of local control is one of the main reasons for the reported poor outcomes.

Since its description by Fortner in the early 1970s, morbidity and mortality of portal and superior mesenteric vein resection has decreased significantly, leading to greater acceptance of venous resection during pancreaticoduodenectomy. In specialized centers, it is now routinely used to achieve a curative R0 resection in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Segmental vein, instead of lateral vein, resection can be performed readily with a primary end-to-end anastomosis, mostly without any graft insertion.

The mesenterico-portal vein resection is planned on the basis of preoperative imaging and intraoperative findings. In case of macroscopic close adhesion between the pancreas and the mesenterico-portal axis, dissection and attempts at separation of the vein should be avoided because of the risk of tumor effraction and seeding, as well as the risk of vascular injury.

Appropriate patient selection is the key to success for a vascular resection in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. High-quality cross-sectional imaging is used to assess solitary vessel involvement, length of involvement, extent of the primary tumor and nodal disease, and absence of distant metastatic disease.

Finally, appropriate selection of the pancreato-digestive reconstruction is essential for a successful outcome of the procedure. A telescoped pancreatogastric anastomosis is our preferred choice, as it is associated with a lower rate of pancreatic fistulas and, subsequently, with a reduced risk of bleeding from the vascular anastomosis. In addition to these basic technical and oncologic factors, the patient's overall performance status, the presence of underlying comorbidities, and overall expectations for outcomes should also be considered.

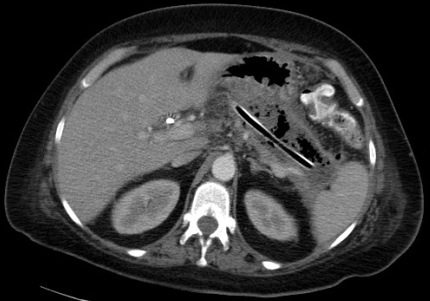

The selected video clip describes the case of a 65-year-old woman presenting with abdominal pain and weight loss (8 kg) without jaundice. There was no cholestasis and the tumor markers, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA19-9, were normal. The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a large pancreatic head tumor measuring 4.5 cm, abutting the superior mesenteric vein with loss of the fatty tissue surrounding the mesenterico-portal axis. The venous phase of the arteriogram showed bilateral narrowing of the superior mesenteric vein corresponding to stage C of Nakao's classification.

Patients are candidates for pancreaticoduodenectomy with en bloc mesenterico-portal resection if they present with isolated macroscopic mesenterico-portal venous involvement and if the surgeon is confident that a tumor-free margin resection is possible. Patients in whom a tumor-free surgical margin cannot be obtained should be excluded.

Adequate exposure is mandatory to safely perform a radical pancreatic resection and additional extended lymphadenectomy. We prefer a bilateral subcostal laparotomy (chevron incision) with an upper midline extension to the xyphoid process. With the use of an autostatic retractor, this provides excellent exposure.

The abdominal cavity is carefully explored to rule out previously undiagnosed peritoneal carcinomatosis and/or hepatic metastases. The presence of such hepatic or extrahepatic disease represents a contraindication to proceeding with resection.

After dissecting the greater omentum from the transverse colon, the lesser sac and the entire anterior surface of the pancreas is exposed. A generous Kocher maneuver with mobilization of the ligament of Treitz (Figure 1) provides full mobilization of the duodenum and the pancreatic head.

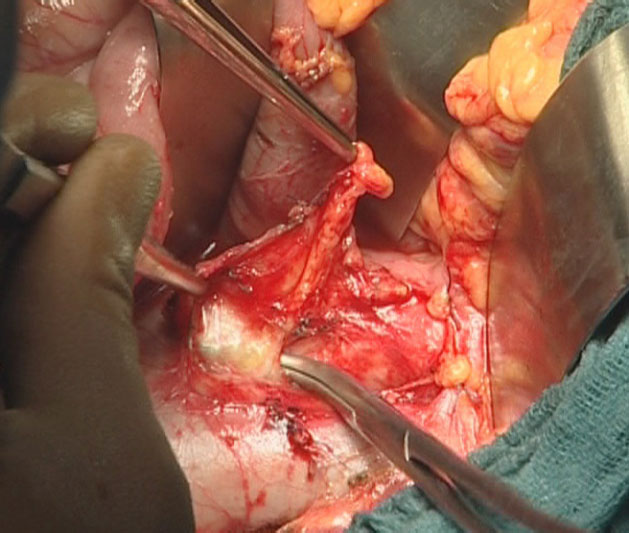

The origin of the superior mesenteric artery just above the left renal vein is identified, dissected, and taped (Figure 2). The location and extent of the pancreatic head tumor is then evaluated, as well as the mobility of the head of the pancreas relative to the celiac axis and the superior mesenteric vessels. The vena cava and the left renal vein are identified. Lymph node sampling in the inter-aortico-caval area below the left renal vein is performed (Figure 3).

At this point, the dissection allows evaluation of the para-aortic lymph nodes, the celiac axis/mesenteric artery, and the mesenteric root. Patients with para-aortic lymph node involvement and/or celiac or mesenteric axis encasement are considered unresectable and will receive palliative treatment, or be submitted to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patients presenting with transverse mesocolon or mesenteric root involvement will undergo extended lymphadenectomy, provided that a R0 resection can be achieved.

Next, the dissection of the plane between the pancreatic isthmus and the spleno-mesenterico-portal axis is performed to identify venous involvement. The decision to proceed with a mesenterico-portal vein resection is made at this juncture of the operation.